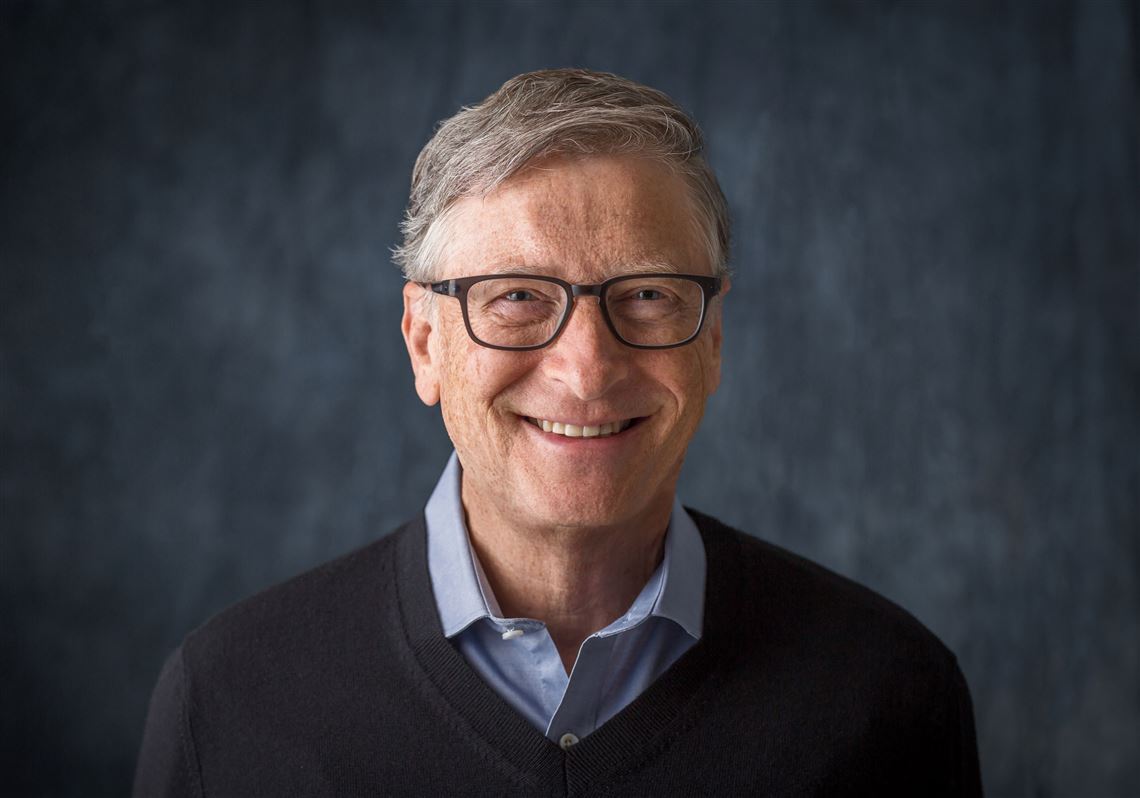

With a possible recession looming, Bill Gates is preparing to raise a new fund for Breakthrough Energy Ventures (BEV) to back innovative climate start-ups, on the heels of two billion-dollar funds that have together helped finance roughly 100 companies.

“Even as the ebullience in investing in tech and climate companies is down a bit, I still think we’ll be able to raise the money,” Gates said on the latest episode of Bloomberg Green’s podcast, Zero. “It’s not quite as easy as it was, say six months ago, but we’re looking at a new round for the startups and a pool under Breakthrough Energy Management that does later-stage investing.”

While companies like Tesla have helped turn the electric-car dream into an increasingly mature reality, and solar and wind now provide cheaper energy than fossil-fuel alternatives, many of the technologies needed to reduce emissions in other sectors are still in their infancy. The $374 billion provided by the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) to support climate- and energy-related technologies is expected to jumpstart innovation geared at addressing those challenges.

Gates hopes that his work with Breakthrough will likewise prompt a transformation of the global economy that gets us closer to a world of zero emissions. Many of the companies BEV currently invests in are trying to scale innovations in carbon-intensive but unglamorous industries, such as low-carbon cement and low-carbon steel.

“Without innovation, you will never solve climate change,” Gates said.

The Microsoft co-founder joined to discuss how BEV is helping steer innovation, as well as his involvement in the IRA, which Bloomberg reported in more detail in August. He also talked about how Europe can tackle emissions while facing an energy crisis.

This is an edited and condensed version of the interview with Gates.

Akshat: In August, you said the Inflation Reduction Act can turn American innovations into American industries. How does the bill do it?

Gates: A lot of the money in there is for things like long duration storage, green hydrogen, better electricity transmission, direct air capture [and] manufacturing processes with zero carbon emission, including cement and steel. In the very early stages, a low-emissions way of making cement will be more expensive, which means that there’s a gigantic green premium.

Akshat: And simply put, the green premium is the difference in cost between doing something in a way that produces greenhouse gasses, and doing the same thing without releasing those emissions.

Gates: Yeah. The magic comes where the green premium gets to zero so that you can tell middle-income countries — which emit 65% of emissions — “This new way of making cement does not have a green premium.” That’s the only way they get to zero, since rich countries aren’t going to subsidize trillions of dollars, and middle-income countries aren’t going to slow down providing basic shelter to their citizens when they know that the rich countries are responsible for the historical emissions.

Akshat: If there was a sector of the technology space that I had to pick out and say that I’ve been flabbergasted, amazed, surprised by the sheer number of ideas coming through it, for me that is carbon removal. Is it a different answer for you?

Gates: I’d say the various agricultural innovations are kind of stunning to me. The basic idea of how nature makes food. For example, there’s funding to improve photosynthesis itself, and engineer it to be twice as effective. I always thought agriculture would be the toughest, but I see a lot of things there.

Akshat: What’s happening here in Europe with the Ukraine war is going to be spectacularly bad for people because of high energy prices. How do you think Europe should be dealing with this while also holding onto its climate goals?

Gates: Yeah, it’s a very scary situation. Sadly, most of the climate things are at best five- to 10-year solutions. So when people say to me, “Hey, we love your climate stuff because we can tell Putin we don’t need him,” I say, “Yeah, 10 years from now, call him up and tell him you don’t need him.” So it’s a very tough set of tradeoffs. Very unexpected. I think in the long run, it’s good for the climate. In the short range, you have to find any solution, even if that means emissions are going to go up. And the sooner that war ends the better, but there’s a lot of considerations that go into how to bring it to an end.

The World Can’t Tackle the Climate Crisis Without New Technologies – Bloomberg